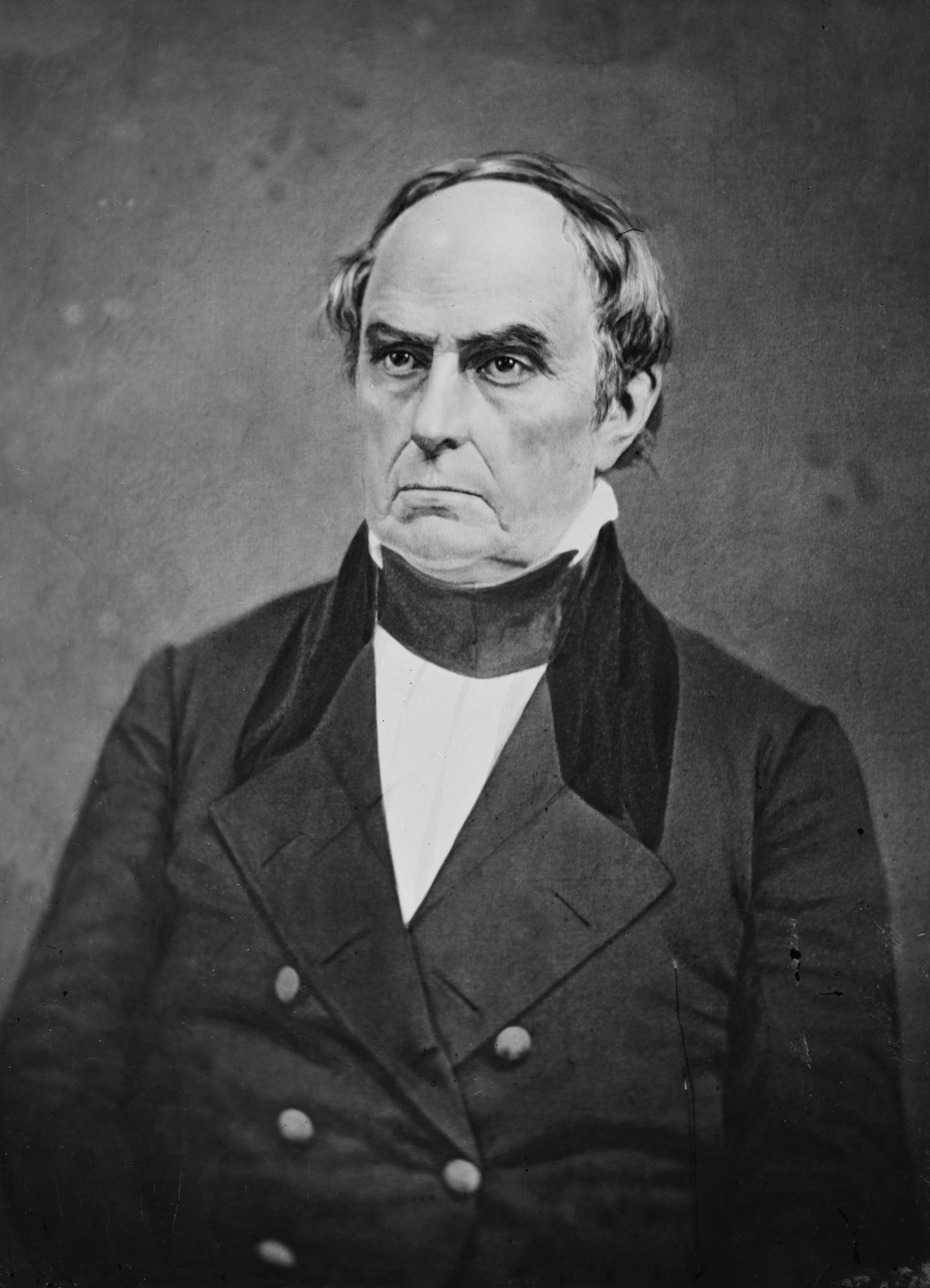

Daniel Webster ( 1782-1852 )

American lawyer and statesman. Born in Salisbury, New Hampshire. Since his student days he was distinguished for his love of public affairs and his eloquence. In 1813 he was elected for the first time to the House of Representatives – it was the beginning of an illustrious political career as representative of New Hampshire and then Massachusetts until 1827. From 1827 to 1841 and from 1845 to 1850 he was senator. Parallel to his political career, he practiced law.

He served as U.S. Secretary of State from March 1841 until May 1843, when he resigned due to falling out with President John Tyler over the annexation of Texas. He returned to office in 1850 until his death, two years later.

An ardent philhellene, Daniel Webster promoted the Greek cause in every opportunity. He was in communication with Edward Everett, a Harvard professor of Greek and an old friend of his from his student days, also an avid supporter of the Greek uprising. On December 8, 1823, voicing his opposition to the Monroe Doctrine, which had been proclaimed a few days earlier, Webster proposed that Congress send an envoy to revolutionary Greece to show its support for the Greek cause. A few days later, on January 19, 1824, Webster militantly defended his proposal in the House of Representatives, in the presence of distinguished guests including Edward Everett himself. He spoke of ancient Greece, reminding his colleagues the extent to which the American democracy had been influenced and inspired by its values, and then focused on the present suffering of Greeks under Ottoman rule. His fiery words were meant to touch the hearts of the senators: “The descendants of that illustrious people, to whom we owe our arts, our sciences... must command our warmest interest: but the Greeks have other claims to our sympathies. They are not only heirs of the immortal fame of their ancestors – they are the rivals of their virtues. In their heroic struggle for freedom, they have exhibited a persevering courage, a spirit of enterprise, and a contempt of danger and of suffering worthy the best days of ancient Greece.” However, Webster’s proposal was not adopted by Congress – US foreign policy at the time was dominated by the Monroe Doctrine of non-intervention in European affairs. Nevertheless, its impact was felt in civil society, triggering widespread philhellenic sympathy by the American people.